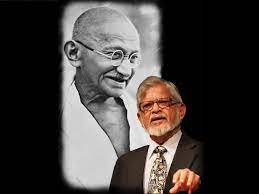

Years ago, I was invited to a dinner to meet Arun Gandhi, the grandson of Mahatma Gandhi. Arun was in Oregon on a speaking tour to promote his grandfather’s teachings. We met in a private room in a restaurant near Pacific University where he wouldgive his talk. There were eight of us at the table. Arun had asked to meet local people involved in peace work, and I was included because of my work with Fields of Peace. Mr. Gandhi was in his 70’s, dark skinned and white haired, handsome and with a strong presence. He was gracious but had about him the authority which comes with a mission. He thanked us for coming, and going around the table, asked each of us about our families and peace projects. The meal was unhurried and lasted long after dessert. Arun and I split a dish of bread pudding. I warned my Hindu friend that there was rum in the sauce. At one point, the table conversation turned to the challenge of raising children in a culture in which so much of our entertainment features violence. TV shows, movies and video games. All the stories sending the same message: Only violence can stop violence, and evil is something outside of us. One of the mothers at the table mentioned how her 7-year-old son, who’d never been allowed a military toy, one evening at supper, chewed the edges of a piece of white bread into the shape of a pistol, then held it up for her to see and smiled. I mentioned that my family lived without television, but somehow movies and games fly through the walls into the bedroom of our teenage son. Arun listened. Then responded. “I grew up,” he said, “in a small Hindu ashram in South Africa which my grandfather had founded. There we followed the principles of ahimsa, nonviolence, and satyagraha, soul force. It was a small, remote community 16 miles from the nearest town. “One morning, my father, Manilal, announced he had a meeting in town, and I was to be his driver. I was delighted. I was a teenager, and terribly bored at the ashram. “On the way to town, my father gave me instructions: while he was at his meeting, I was to take the car to the garage for maintenance, and shop for the week’s groceries. He handed me a list. When I dropped him off at the courthouse, he told me to pick him up at 5 0’clock. “Well, there was a John Wayne movie in town. A forbidden entertainment. But I wanted to see it, and there was a matinee. So, I dropped off the car, and hurried with the groceries, and made it just in time for the movie. “As it turned out, it was a double feature. And when I walked out, it was already 5:15. I ran to pick up the car and raced to the courthouse. Promptness was religion in my family. There stood my father on the curb. ‘What kept you?’ he asked. ‘They were late with the car repair,’ I said, ‘so I had to wait.’” ’I called the garage at 5,’” he said. ‘The car was ready, but you weren’t there.’ He looked at me. ‘How is it I raised a son who is a liar?’” “’You drive home,’ he said. ‘I will walk.’” Arun explained that in his family and culture, when a child did something wrong, it was the parents who did the penance. “If I or my siblings misbehaved, my mother and father would fast for a day, or several days. Mother would cook and serve us at the table, but she and my father would not eat. “So,” Arun said, “my father began the 16-mile walk home. For a while I trailed behind in the car. Night came. And finally, I couldn’t stand it any longer and drove on home.” It was quiet at our table following his story. And soon after we adjourned to go to the auditorium for Arun’s lecture. But his story stayed with me. From my modern, western perspective, the idea of a parent making penance for their child’s wrongdoing seemed emotional blackmail. A heaping on of guilt. In the days that followed, I thought about Manilal on his long walk home. I tried to imagine his painstaking self-examination and prayer. I also thought about young Arun, his dismay and pain as he, from the car, watched his father walk on and on. I grew curious about the wisdom of Manilal’s approach to moral formation, and how it followed his own father’s philosophy and example. I recalled Gandhi’s insistence that the means, in pursuit of change, must resemble the end one envisions. Justice requires just means; peace requires peaceful means. In our moral quests, however, we never reach perfection. So, the means, moment by moment, are the end we live with. Change brings suffering, whether it is change of an entrenched system or personal behavior. To be confronted with one’s own wrongdoing can bring shame and a crisis of conscience. Confronting the status quo can bring bloodshed. The question is: Who will do the suffering? Gandhi believed that voluntary suffering, as opposed to reasoned argument, is the most effective way to change the heart of another person or an entire people. This belief became a practice which he lived. A few examples: *In 1913, Gandhi fasted for 7 days as penance for the moral lapses of two friends in his Phoenix Ashram in South Africa. *In 1924 he fasted for 21 days in the home of a Muslim friend as penance for the recent violence of Hindu’s against Muslims. He encouraged Hindu’s to “do the dying not the killing.” *In 1932, he fasted to protest against the designation and segregation of “untouchables” in the proposed new Indian Constitution. He wanted “to sting the conscience of the Hindu community into right religious action.” *In 1948, Gandhi declared a fast unto death as penance for the communal riots fueled by the partition. He hoped to restore a lasting peace in the hearts of Hindus and Muslims. Manilal’s penance for Arun’s lie follows the teaching and practice of his father. In the 16-mile walk home, Manilal examined himself for ways he may have failed his son through lapses in honesty and kindness or judgement. By this example, he sought to bring his son to self-examination. By this suffering, he sought to open his son’s heart and bring transformation. The fact that Arun, so many years later, shared his story with us, points to the effect his father’s penance had on him. Through Arun’s story, I’ve come to see something profound in the practice of doing penance for a child’s wrongdoing: It is the gift of one’s self that delivers truth. I also appreciate the humility implicit in this practice, a humility likely to include remembrance of the stumbles of one’s own youth. In his autobiography, My Experiments with Truth, Gandhi tells how he, as a teen, started smoking cigarettes and stole money to pay for them. Before long, he could not stand himself, and decided he must change. Gandhi writes: I decided at last to write out a confession, to submit it to my father, and ask his forgiveness. I wrote it on a slip of paper and handed it to him myself. In this note not only did I confess my guilt, but I asked adequate punishment for it, and closed with a request to him not to punish himself for my offence. I also pledged myself never to steal in future. I was trembling as I handed the confession to my father. He was then suffering from a fistula and was confined to bed. His bed was a plain wooden plank. I handed him the note and sat opposite the plank. He read it through, and tear-drops trickled down his cheeks, wetting the paper. For a moment he closed his eyes in thought and then tore up the note. He had sat up to read it. He again lay down. I also cried. I could see my father’s agony. If I were a painter, I could draw a picture of the whole scene today. It is still so vivid in my mind.

– By Charles P. Busch